On Death, Writing and a Vanished Wedding Dress

My father died on November 11th, 2021. It was not unexpected, but it was traumatic in the way that only losing a parent can be. The prior April had kicked off a series of hospital and rehab stays and my brothers and I had ultimately made the decision to move our father from his beloved New York City to a skilled care facility in Cleveland near my younger brother. Dad seemed to be thriving there, making friends with caregivers and other residents; my brother and his family were able to visit often even with Covid protocols in place.

It was while I was at LAX waiting to board a flight to Cleveland for a long-planned four-day visit that I got the word: Dad had taken a sudden turn and could no longer breathe without assistance. Given his living will, we were advised to put him in hospice care as soon as possible. I boarded the plane knowing that all of our simple family plans for the weekend were now suddenly and tragically upended.

Five endless days and nights passed as I stayed mostly by his bedside. I was there when he drew his last breath. It was a beautiful and awful privilege to have spent these last timeless days by his side.

Then there were arrangements and ritual. And grieving. It was frankly a terrible time, complicated by the fact that I was in the midst of finishing my novel PRIVACY. A work begun during the darkest days of Southern California’s Covid lockdown, the question at the heart of the book is how much pain can we bear before we break? People all around me were grappling with death and loss and fear. I was struggling myself and I’d found personal real-world solace, as I always do, in puzzling out the breaking points of my fictional characters. But the final stages of the book marched along with the final days of my father’s life. Watching his decline and death as I copyedited and battling my grief as I wrote acknowledgements, I had to recognize that this book that was born during a dark time was also finishing in one.

After my dad died, I mourned, but I couldn’t make the trek from Los Angeles to New York to confront the detritus of my parents’ lives and empty their apartment until March of 2022. My mother died back in 2016, but while my father insisted their place be denuded of her personal effects almost instantly (seeing her things was just too painful for him), most of their combined worldly possessions were still in their Long Island City apartment.

When I finally cleared the time and space to go, I committed two weeks to the task, knowing that I’d need to juggle work obligations while confronting the boxes of photographs, the cabinets laden with dishes and appliances, the shelves full of books, the closets full of clothes, the stacks of paperwork and the drifting, ghostly memories.

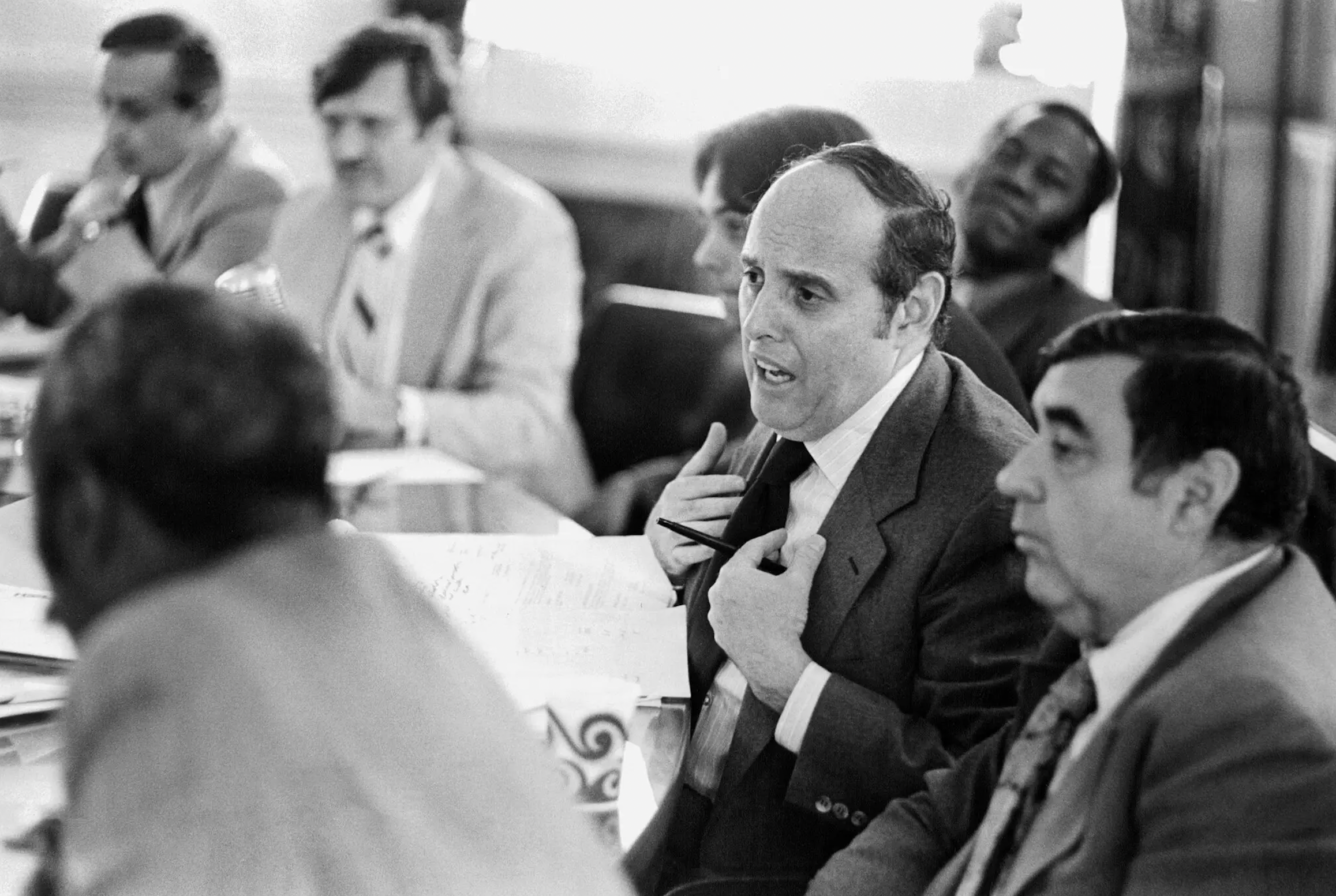

There were treasures (a commemorative key from when my father was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Miami in 1972) and a lot of trash (I don’t think my mother ever threw out anything as she operated under the tried-and-true theory of “you never know when it might come in handy”). There were relieved shudders as I dumped the painful accoutrements of illness and decline, and pleased smiles at finding delights like a slight naughty love letter my father had written to my mother when they were newlyweds. It was a decidedly mixed experience but overall, the process was arduous physically and exhausting emotionally.

A particularly fraught find was my mother’s wedding dress. It had become mine when I married, my mother insistent of that tradition even though I was a full six inches taller than she, and she had been a December bride, while my ceremony was planned for June. For love of my mother, the dress was altered to fit me (additional lace in the bodice changing the shape from a dropped waist to a nipped waist) and I endured the heavy satin skirts and long sleeves at an outdoor ceremony on an unusually hot June afternoon.

But at least the dress had good juju as my parents’ love story was epic: married within weeks of meeting and still madly in love until death did them part over sixty years later. One of my favorite photos from my wedding day is a close-up of my mother’s hands fastening the tiny buttons that ran up the dress’s back.

On March 31st, I packed up four boxes, one containing the wedding dress (along with a few assorted knickknacks), to send back to LA and lugged them over to UPS for shipping. I declined the extra insurance; there was little of actual value in the boxes, although of course the sentimental value of the items was enormous. Anxiety fluttered in my belly as I made this choice, but it seemed the right one.

I flew back to LA on April 1st. Three boxes arrived on April 5th, but one box was missing and thus my hounding of UPS began. The missing box happened to be the one that held my mother’s wedding dress, the dress I had also worn to marry my first husband, the father of my children, and this seemed suddenly and inexplicably important. UPS kept telling me to “check back in,” for more information but the box seemed to have disappeared.

On April 19th, Death Cleaning’: A Reckoning With Clutter, Grief and Memories ran in the Times and I deeply related. I shared the article with other recently bereaved friends and I redoubled my efforts with UPS. I had suffered through the painful death cleaning, wasn’t I entitled to the few things I had scavenged for sentiment?

On May 12th, I got final word from UPS. The box was officially lost. No record. No history. No ideas. I burst into tears. I wailed at the UPS employee, indignantly demanding to know what I was going to tell my daughter when she asked to wear the dress. The employee was kind but resolute: I’d receive the standard $100 insurance claim and a refund of the shipping costs. I was devastated. My tears flowed for over an hour, even as I repeated to myself over and over again: “it’s just a thing.” The loss of the wedding dress (which to be fair, neither my son nor my non-binary child are ever likely to ask to wear) triggered a deeper well of loss, a boomerang of mourning that encompassed all of my grief about the death of both my parents. Pondering the depth of my response, I realized there's an expectation that physical objects are here to stay. We know people will die, but that possessions might have a "death" too, particularly meaningful, generational ones, was an unexpected shock. The expectations of my mother’s wedding dress had already been upended in several ways––my first marriage didn't work, it’s unlikely the next generation will wear it, and now as it turned out, its physical presence was also never guaranteed.

As with all things painful, I knew I had to write out the emotions with which I was grappling, and so here I am. It’s my deepest hope that this tale’s publication will bring about a kind of magic, a happy ending to my story of loss. I envision UPS workers inspired by my tale dutifully checking every stray or unlabeled box in pursuit of the dress and in support of our reunion. I imagine the dress mistakenly arrived on someone else’s doorstep just when they needed a wedding dress, so while they are now planning on wearing it, they will also now know to send it to me after their nuptials. I dream of a miracle, even while I know I should scoff at my own romantic notions. But that’s the thing about loss, we all need a story, a hope or dream to give us back our purpose and allow us to keep on going. It’s why as I was making the final edits to my new novel, I dedicated the book to the memory of both my parents; it was part of the way I was able to keep on going.

Will I ever see the wedding dress again? A woman can hope. If there are any UPS workers out there reading this, please keep your eyes wide open. And if the dress has found its way to a needy bride, may it bless you with my parents’ kind of love.